An author’s persona and mystery can add layers to their work that are hard to strip away from the written words on the page. But what happens when a reader comes face to face with their literary icon? Can it inspire beautiful prose or leave a bitter taste of disappointment?

By Sarah Hollister, co-author of This Land is No Stranger

The house stands on the side of a low mountain in the northwest of Sweden in the province of Härjedalen. The first time I was given a residency here, I mistakenly believed it was Henning Mankell’s childhood home.

Sensing what I believed to be his spirit, I wandered the rooms, tried to decide which of the three bedrooms on the second floor was his, imagined him as a child standing on the balcony, taking in the sweep of forest and water that lay in the valley far below.

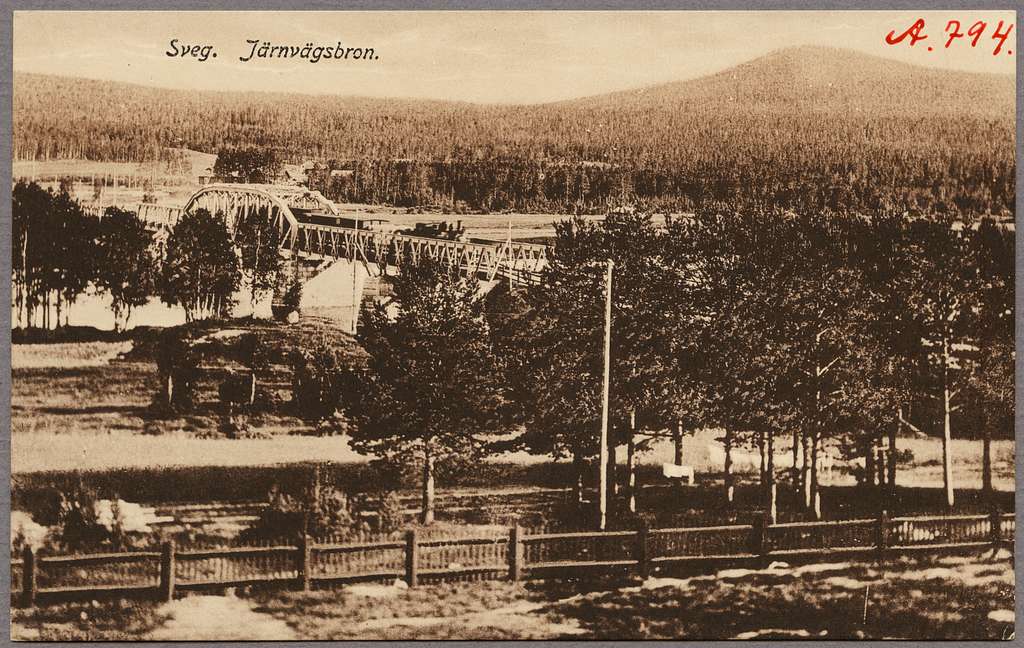

A Google search later revealed Henning Mankell bought the house in 2007 and gifted it to the two writer’s guilds: Dramatikerförbundet and Författarförbundet. He grew up in the nearby town of Sveg on the second floor of the Tingsrätt (courthouse) where his father, the judge, presided. And although his Kurt Wallander detective series is situated in southern Sweden, Skåne, a more benign landscape, flat and physically uneventful, the prototype of the farmhouse where the unspeakable, the horror, is inflicted upon the inhabitants, could be found here in the rough nature of Härjedalen. (The word härjae means to plunder and kill.)

Through a window before going back to bed, I watched the moonlight reflect on the snow, the air brightening, a softness all around and feel a sense of peace. I remember a story that Henning Mankell tells of his early recollection of snow, of the glimpse of a black dog running that catches his eye through a window, the mystery of snow, the magic of it.

The mystery of snow

In the morning, bright sunlight and sparkling icy hoarfrost greet us. The view is glorious: in the distance, a lake and beyond forest-covered mountains, everything covered in white, above it all, the bluest sky. I build a fire and we drink morning coffee, a routine we settle into in the coming days.

While there is light (from 9 o’clock to half past two, more or less), Gunnar explores the forests and paths taking photographs of the icy brilliance, while I keep the fire going and content myself with short walks up the small country road.

I remember a day when I might have spoken to Henning Mankell. The Kulturhus, a glass and steel structure in the center of Stockholm, a warehouse of theatres, art exhibits, restaurants, cafes was celebrating the centenary of the Swedish playwright, August Strindberg. Henning Mankell was presenting the premier of a one-act play he had written about Strindberg and I stopped by.

I remember him that day looking as I had often seen him look in the familiar jacket-cover photographs on his books: a mane of pure white hair, a dark suit, always a necktie. His hair was thinned but still distinctive. His face in profile perhaps more fleshed out than it had been in his earlier life. I remember thinking the tan shoes he wore should have been dark to match the suit.

I watched as people approached him, shook his hand, moved on. Watched as he appeared to check the stage, engaged but accessible.

One opportunity

Then he was alone. I had only to cross the short distance between us to tell him something. But what: that his Faceless Killers was the first book I had read in Swedish. That I recommend my English language students read his books in English because as they are written in Swedish so are they translated, in the pure and clear prose style of the original. I wanted to tell him I admired him. I wanted to thank him for taking risks with his life, for going on the first Ship to Gaza to break the Israeli blockade. For his work in Africa with theatre and street children. For championing the underdog and the oppressed.

I left that day feeling both disappointed and relieved. Fearing I would stumble over words, embarrass him and myself, I had sat glued to my seat.

The abandoned houses of Härjedalen

One day I go with Gunnar and we cut off the road, following a path deeper into the forest. Through thick, snow-covered pine branches we see an abandoned house. An old car, a Ford, is parked in the driveway, the hood of it propped open, a silvery glaze of thick frost making the metal once more shiny and new.

Stomping snow off our boots we enter the house, though it doesn’t really matter. There are broken windows where the snow and rain has poured in over the years. There is furniture toppled over, bits of broken crockery cover a wooden table. On the wall of an enclosed staircase, a white high school graduation hat hangs, eloquent, on the wall. As if the family left in the night, rushing, leaving behind. Vandals have covered one of the walls with unintelligible text. A sense of decay lingers, the house gathering mould and rot.

How many abandoned houses exist up here is hard to say. Surely it’s more difficult to make a living now than when Henning Mankell was growing up in the nineteen fifties. Earlier than that in the mid-eighteen hundreds, people were starving to death. Hard winters were followed by several summers of what they call a “green winter”, summers wherein the ground stays frozen, impossible to grow even a potato.

Those who could do so left, becoming part of the mass emigration of Swedes to the United States.

By early afternoon, the sun begins its downward descent. In the darkness, the house closes around us, welcoming, warm. Nothing is required of the writer at this residency; families are welcome. A long wooden dining table stands just off the kitchen. The cupboards there are place settings for twelve or more people, deep bowled wine glasses. In one of three spacious bedrooms, a baby crib is tucked in a corner

Later still, I stay up reading Quicksand. Homo narrans, the Latin words he uses in respect of the human condition: the ability, the need, to tell stories. Stories unfold; in several he recounts a death he has witnessed, in others he tells vibrant stories of life in Africa and Sweden. What the essays reveal is the writer himself, what has fascinated and fulfilled him during his life. There is evidence of unending curiosity and intense interest in the world around him, the people he has met and those he has not.

A one-horse town

His childhood was a happy one, writes Henning Mankell. His days spent exploring the wild nature of Härjedalen, the forests and lakes, the beauty of the River Ljusnan flowing down from glaciers in Norway, he says, had the most influence and also the happiest.

Sveg, the town of narrow, short streets Henning Mankell wandered as a boy, is pretty much a one-horse town. With just over 2,500 inhabitants, not much happens. Though Gunnar and I look forward to our daily afternoon jaunt into town for a coffee at the local grocery store, a chain that dominates every Swedish town. The coffee shop is lively on account of the gambling, people lining up to place their bets, a feeling of an imminent win permeates and the coffee is strong and good.

At the library, there is a room designated the Henning Mankell kulturcentrum. On the walls, there are black and white photos of Africa, of scenes from the productions he directed at the Teater Avenida in Maputo. Copies of his books line the shelves. Artfully arranged are copies of several of translations of the Wallander series, in Polish, French, Chinese. In sum the books were translated into 40 languages. Doing the math, 40 languages, 40 million readers, the reach of his words. Impressive…

The art of listening

What is a storyteller without the listener? How do we understand the “other” without the act of listening?

In an opinion piece in The New York Times entitled “The Art of Listening”, Henning Mankell told a story, paraphrased here:

Outside the Teatro Maputo, he shared a stone bench with two old African men one day, listening as they talked about a third old man who had recently died. One of the men, visiting him at his home, had heard the beginning of an amazing story from the dying man but had to leave before he heard the end of it. When he arrived the next day, the man had died.

“That’s not a good way to die — before you’ve told the end of your story,” said the other man.

Homo narrans is the name of the film the Swedish filmmaker, Stephan Jarl, made about his friend, Henning Mankell. Released after Henning Mankell’s death, it is a testament made in the last days of his life and in it, we see him, though worn, still vital, still using the word solidarity, still telling stories in his calm, measured voice, something humble, kind, in his bearing.

Perhaps the film was, for Henning Mankell, a way to end his story. What he leaves behind are his words, his stories, his acts of courage, his call to take heart in a world that seems in these times to have lost its way.

At the end of the film, we see a man from a distance. He is dressed for a chilly day, walking the length of a wooden dock stretched out into the water. The scene is leached of color, or maybe it is once again the heaviness of clouds, the lack of sunshine. He takes his time, reaching the end seems a long way off. Around him lies the water, edged by a forest of pine. As he nears the end of the dock, dissolve and the man vanishes.